"It was not exactly difficult going, but it was a dangerous place for a single unroped climber, as one slip would have sent me in all probability to the bottom of the mountain."

– Colonel Edward “Teddy” Norton

Many volumes have been written about the 1924 Mount Everest Expedition, most of which have focused, understandably, on the tragic and mystery-spawning disappearance of George Mallory and Andrew Irvine. Their final climb, and ultimate disappearance, is fascinating, and more than worthy of the attention it has received.

But, that was not the singular moment of the 1924 Everest Expedition. In fact, four days before Mallory and Irvine’s disappearance, a remarkable record was set by their teammates, Howard Somervell and Edward “Teddy” Norton.

Ninety years ago today, on June 4, 1924, Norton and Somervell awoke to the dark and unforgiving cold of early morning at Camp VI on the North Ridge. Their hope for the day was to get an early start and climb to the summit without supplementary oxygen; both Norton and Somervell felt oxygen – especially with the primitive delivery system of 1924 – was an unneeded crutch, an ethical shortcoming, and simply not worth the weight and hassle. Their day quickly got off on the wrong foot, however, when Norton realized one of his thermos flasks of warm tea, which he slept with to keep from freezing, “had got rid of its cork, and its contents – no longer warm – had emptied into my bed.”

But, true to character, the two climbers rallied, fetched more snow to melt into water, and were off from Camp VI at 6:40am. (I’ve long wondered if the lone sock – marked with a tiny label reading “Norton” – I found in the remains of Camp VI in 2001 was a casualty of this thermos accident and abandoned by Norton in favor of a dry one.)

Along with oxygen, Norton and Somervell differed from George Mallory in choice of route. Rather than following the crest of the Northeast Ridge which Mallory advocated, Norton and Somervell viewed a traverse across the North Face and into the Great (Norton) Couloir as the better option. As Norton wrote in The Fight for Everest, 1924: “a feature on the skyline ridge which we called the second step…looked so formidable an obstacle where it crossed the ridge that we [chose] the lower route rather than try and surmount it at its highest point.” So, Norton and Somervell continued traversing the great North Face of Everest, following relatively easy terrain from the Northeast Shoulder. They hugged the base of the Yellow Band and found the early morning weather “fine and nearly windless” yet “bitterly cold”.

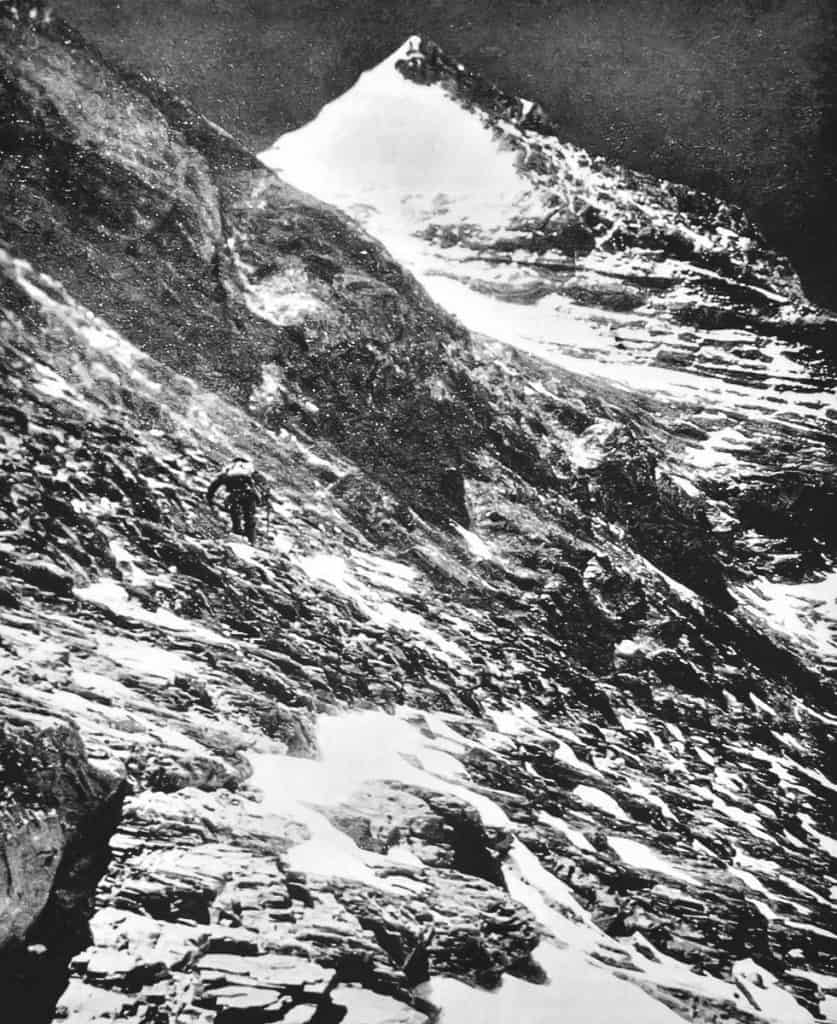

By midday, Somervell was overcome by the effects of his sore throat – exacerbated by the cold and extremely dry air of high altitude – and told Norton to continue along without him. Norton did so, following the contour of the lower Yellow Band. Norton describes the terrain: “From about the place where I met with these buttresses [coming down from the Second Step] the going became a great deal worse; the slope was very steep below me, the foothold ledges narrowed to a few inches in width, and as I approached the shelter of the big [Great] couloir there was a lot of powdery snow which concealed the precarious footholds…I had twice to retrace my steps and follow a different band of strata; the couloir itself was filled with powdery snow into which I sank to the knee or even to the waist, and which was yet not of a consistency to support me in the event of a slip. Beyond the couloir the going got steadily worse; I found myself stepping from tile to tile [of rock], as it were, each tile sloping smoothly and steeply downwards; I began to feel that I was too much dependent on the mere friction of a boot nail on the slabs. It was not exactly difficult going, but it was a dangerous place for a single unroped climber, as one slip would have sent me in all probability to the bottom of the mountain.”

Feeling he was stepping beyond his risk tolerance, Norton at this point decided – with a combination of disappointment and relief – to turn around and return to Somervell. While unsuccessful in reaching the summit, Norton’s climb was heroic, and record setting. His final altitude was roughly 28,126 feet, climbing in woolen knickers and a tweed coat and without oxygen. To give an idea of how remarkable this was, no one would climb higher than Norton without using oxygen until Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler climbed Everest by the Southeast Ridge without oxygen in 1978.

Norton returned to Somervell, who was waiting in the same spot, the the duo began their long descent to Camp IV at the North Col. Along the way, Somervell continued to battle his worsening throat. As they hit the snowslopes of the North Ridge, he fell behind Norton who continued on unaware. Thirty minutes later, when the two rejoined, Somervell recounted coughing so badly he began to choke and quickly became fearful he would die; acting quickly, he gave himself a sort of Heimlich using his arms and a section of tent pole from Camp VI (he had dropped his ax down the North Face earlier in the day) and, as he said, proceeded to cough up the lining of his throat. After nightfall, Norton and Somervell approached the camp at the Col and, after shouting for some time, were greeted by Mallory and Noel Odell and escorted back to the tents.

And so ended the second – and perhaps best – attempt on Everest in 1924. And, if the above story hasn’t impressed and humbled you enough about the skill and strength of these climbers, take in another anecdote from Fight for Everest shared by Norton. Early in the day on June 4, as they left Camp VI, he found himself shivering so violently against the cold that he “suspected the approach of malaria”. He stopped quickly to take his pulse and “was surprised to find it only about sixty-four, which is some twenty above my normally very slow pulse.” Heartrate of 64 beats-per-minute, at over 27,000 feet, under exertion, in extreme cold, and without bottled oxygen.

Amazing.

Colonel Edward “Teddy” Norton

Howard Somervell