After reading Part I of this story, we’re all essentially on the same page with what we know about the story of George Mallory & Andrew Irvine.

Now, the fun part: What do we, or more precisely, what do I, hypothesize happened to them on that fateful day, June 8, 1924?

Let’s begin…But first, a bit of reference for you. Below is a Zoom.It photo of the North Face of Everest with some key features marked. It is pretty high-resolution, as you will see, composed of about 20 shots I took in 2004 and stitched together. (Apologies in advance for the lack of dust removal…Too many specks to deal with!)

Knowing the virtues of an alpine start, Mallory would have insisted that the pair get an early start to the climb toward the summit. However, we know that they could not have left too early in the day – not before the first light of dawn illuminated the landscape – because their teammate, Noel Odell, found their head torches left behind in Camp VI. But, we can safely assume that they left sometime around first light, which would have come at roughly 4:30 AM. (While the sun hasn’t risen at this point, in my experience it is more than bright enough by 4:30 AM to move without artificial light.)

Climbing upward along the North Ridge, Mallory & Irvine would have encountered little difficulty en route to the Northeast Shoulder. Scrambly rock, similar to that of the lower North Ridge, is the only challenge…along of course with the extreme altitude.

From the Northeast Shoulder – having stood there myself in 2004 and gazed upward at the possible route options – they would have taken the most prominent and obvious line up through the Longland Traverse and on to the Northeast Ridge via the upper section of the modern “climbers’ gullies”. Again, the climbing, while interesting, is never very difficult in any part thus far and I’m confident they would have covered it relatively quickly and efficiently. Additionally, the route finding is minimal as the Longland Traverse to the climbers’ gullies is the obvious path from the Northeast Shoulder to the Northeast Ridge. (You can see a video I shot from here in 2004 on YouTube.)

Once on the Northeast Ridge, things for Mallory & Irvine would have inevitably gotten more, well, more interesting. Being ridge climbers, their habit would be to stick to the ridgecrest as much as possible. But, massive cornices overhanging the daunting Kangshung Face would understandably push them away from the crest from time to time as they moved toward the summit. The first obstacle would come after about an hour on the Ridge: The First Step.

Roughly 60 feet of rotten rock and crumbling snow, the First Step causes little more than a spate of breathlessness for climber’s today, who have the fortune of a known route that is well fixed with rope. But, for Mallory & Irvine, it would be a different story. Take the ridgeline, or the middle route up steeper rock? Try to circumvent the Step as a whole, cutting down onto the North Face below the Gray Band?

Again, being ridge climbers, my bet is they would have taken the ridgecrest. I investigated this option in 2004, and found it to be quite reasonable and well within Mallory’s climbing ability. Soon, they would be on top of the First Step, looking at an inspiring – and daunting – view.

From the top of the First Step, one gazes upward at the enticing and alluring summit. It seems close at this point, tantalizingly close. But, you also see from here the at-times-impossibly-serrated Northeast Ridgecrest slicing skyward with fin-like cornices and imposing rock bands. Most impressively, from here you see the great Second Step, an 80-foot saw-toothed jag of rock sticking like a ship’s prow out of the ridge. Daunting today…it must have been terrifying in 1924.

But, again, just behind the Second Step, the summit looms, luring like a siren song. Despite the perhaps slower pace than they had anticipated, I’d be willing to bet Mallory & Irvine pushed on.

Again, the desire to climb the ridge directly would be at odds here with the topography. Cornices, steep jags of rock, and enticing “sidewalks” of limestone all force one downward, off the ridge and onto the North Face. But, that’s not where Mallory & Irvine wanted to go. On June 4, 1924, Teddy Norton and his companion, Howard Somervell, chose to keep off the Northeast Ridge, thinking the Second Step posed too great of an obstacle. They instead traversed the North Face to the Great Couloir, where Norton was finally turned around at 28,165 feet. Seeing Norton’s failure, I think Mallory would have been inclined to give the Ridge a try and see what lay in store.

(Note that Norton and Somervell were climbing without supplemental oxygen. Norton’s oxygenless altitude record would stand for 54 years, until it was bested by Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler in 1978 when they climbed Everest without oxygen. Amazing.)

So, they climbed on, tiptoeing along the knifeblade, scurrying around boulders and across narrow, harrowing traverses. They passed Mushroom Rock which, at 28,100 feet, is the gateway to the Second Step, and a good resting point.

Where to go from here? I can only imagine how vexing this question must have been for them. Directly ahead, along the ridge, cornices sweep wildly outward, their great fins of snow hanging some 40-50 feet over the Kangshung Face. Slightly right, to the west, thin bands of rotten rock angle below the ridge into unknown terrain. Again, this is an easy point for us modern climbers: fixed lines guide the way and tell us everything but where to put each foot and how often to breath. But, not so for Mallory & Irvine. This was no-man’s land. And an unforgiving one at that.

My bet is that they first tried the ridge itself, treading a fine line between the rock and the snow moving toward the Second Step. But, this attempt would, I think, soon end when the icy crest of the Second Step came fully into view, a vertical, thin jag of corniced snow overhanging the Kangshung Face. Not appetizing today, and not in 1924.

Now, a frustrating about-face, with Mallory & Irvine retracing their steps back to Mushroom Rock.

What do they do here? It’s getting late. They are tired, and running low on oxygen. The weather is far from perfect, with pre-monsoon squalls buffeting the mountainside.

But, there ahead lies the Holy Grail, the summit of Everest…It seems so close, so tantalizingly close. Fame, fortune, glory, security…All of it was wrapped up in that summit, that patch of snow, for Mallory, and to some extent for Irvine. As a friend of mine said, the only way home for Mallory was, strangely, via the Top of the World.

Thus, I think they pushed on. I think, despite the lateness of the day, despite the fatigue they must have felt throughout their bodies, despite the fact that they were low on oxygen…despite all of these things, all of these things that Mallory’s years of experience in the mountains had taught him…I think they pushed on. I think Mallory had to push on. As his friend, Geoffrey Winthrop Young wrote, Mallory would not have turned around high on the Northeast Ridge – could not have turned around – simply because Mallory was Mallory.

And, I’ve been there myself. In 1999, I was at Mushroom Rock with Dave Hahn, Conrad Anker, Tap Richards, Ang Pisang Sherpa, and Dawa Sherpa. It was too late in my estimation to continue climbing and leave a window of safety for our return. Storms were creeping in, clawing up the valleys from Nepal. But, there was the summit, luring me onward. It was a climb I had dreamed about since I was 8, and finally, after a long 17 years, I was there, close, almost to the top. Making the decision to turn around – which I know was the right one for me that day – was agonizing, heart wrenching, the hardest decision I’ve ever had to make in the hills.

And, I wasn’t in position to be the first. I didn’t have an entire nation waiting with baited breath for me to reach the top. My reaching the summit would not have meant financial security for me and my family. Mallory, on the other hand (and to a lesser extent, Irvine), had all these pressures, and probably more.

So, they pushed on, they got summit fever. It wasn’t smart, it wasn’t noble…It was a sad decision, a regrettable one, but strangely understandable.

Taking a new route, investigating the natural lines of the mountain, they follow the strata slightly westward, off the ridgecrest and into the clefts of the Second Step. Here they see an option, a choice: leading to the west, onward in a traverse across the face, are the strata, which seem to lead out to the Great Couloir. Again, knowing what Norton encountered four days before, they don’t want to repeat his efforts. But, just to the left of them they see a break, a weakness in the defenses of the Second Step…but not much of one.

Just above, wind sculpted rock corkscrews upward to a snowy platform below a final, 15-foot, imposing headwall of vertical rock which leads to the top of the Second Step. Not easy, not simple, not secure, but a weakness, an option, a possibly opportunity. Being a skilled rock climber, one of the best of his generation, Mallory moves toward it with Irvine in tow, roped up behind. The Corkscrew Chimney, as we call it today, is awkward and exposed. There is no grace when ascending it – at least not for me – but rather a lot of grunting and scraping and swearing and clawing. But, it’s not really hard either – just awkward and exposed. And, this is perhaps the one area where a tweed coat and woolen knickers might have had a distinct advantage over a down suit: Mallory & Irvine could have seen their feet, whereas we modern day climbers are warm, but our view from the waist down is revoked by piles of down and nylon. I think, with that slight advantage, Mallory would have moved through the Corkscrew with relative ease and, from the final snow platform before the headwall, would have belayed Irvine up to him.

And now the “fun” began. Fifteen feet. Steep. Exposed. An off-width crack to the left. A crumbly, angled crack to the right. Ten thousand feet of air directly below. No chance for a mistake. No room for error. No second chance. What on earth did they do here?

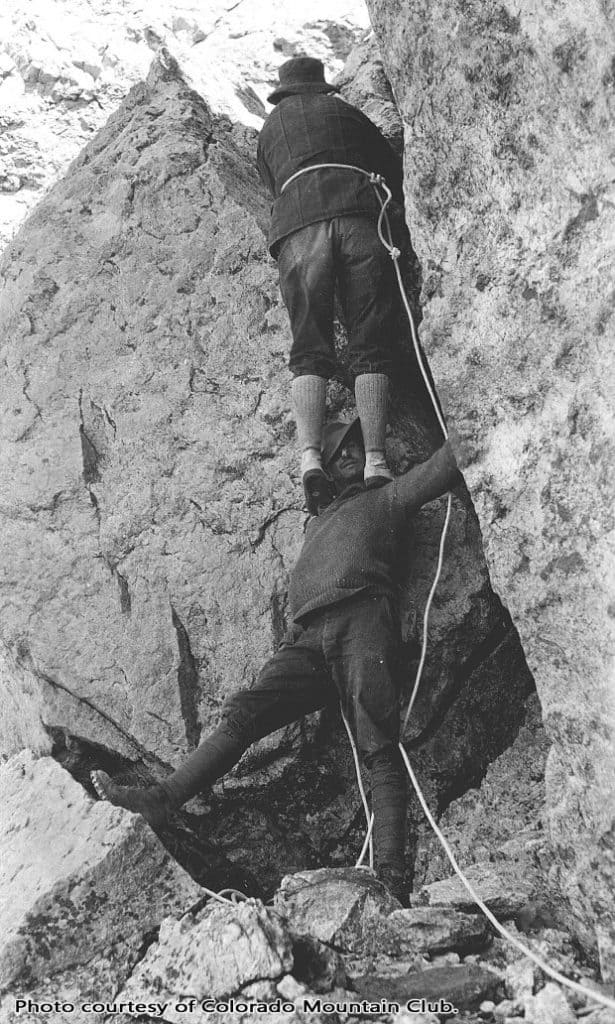

The answer never dawned on me until I started working for the American Mountaineering Museum in late-2007. My friend, Chris Case, was editing a new brochure for the “Friends of the Museum”, and chose as the cover shot a perfect image: legendary Colorado climber Albert Ellingwood scaling a steep section of rock in the 1920’s by means of the shoulders and then the head of his climbing companion, Carl Blaurock. The technique is known as a “Courte-echelle”.

If one were to use this technique at the crag today, you’d be booed and chastised and laughed at. It is simply not acceptable technique by today’s climbing standards. But, in 1924…things were different. (This technique was noted by Ullman in Kingdom of Adventure, and also appears in a 1945 issue of Life Magazine.) And, they were especially different in 1924 at 28,300 feet on the Second Step.

Andrew Irvine, standing at over 6 feet tall, would have been a good series of hand and foot holds for Mallory. With his feet planted firmly on Irvine’s head, Mallory could just reach the top portion of the Step, the point where it gets slightly less steep and some handholds appear. From there, a few scary, exposed, dangerous moves would have helped Mallory collapse, exhausted and exuberated, atop the Second Step.

(Of note is the fact that the first known ascenscionists of the Northeast Ridge – the Chinese in 1960 – used exactly this technique to get up the Second Step. The lead climber, Qu Yinhua, actually took off his boots and gloves to make it happen, eventually losing his hands and feet to frostbite…but getting through the problem nonetheless.)

Using the rope, Mallory would have belayed Irvine to the top of the Step for a well needed rest and to reconnoitre the next phase of the climb.

And from here, it was comparatively easy. The top of the Second Step leads along easy ground to the Third Step, which, once upon it, shows itself to be of little problem: a short, easy scramble leads through it to the snow slopes above.

Another 45 minutes would lead Mallory & Irvine to another choice: follow the snow directly up steep terrain, or break out onto the North Face? Although steep and daunting, I think they would have opted for the snow. They’re tired, it’s late, and they’re amazingly close now. They don’t want to risk going off to the west-southwest along possibly easier ground only to encounter another obstacle, one which they cannot surmount. So, they go straight up.

Mallory leads, agonizingly cutting steps in the styrofoam snow. It is steep, but not more so than sections of the North Col Headwall. Slowly, carefully, painstakingly, they make their way to the top. And, there, they see a great sight: the summit, the grail, the top of the world, just minutes away. It’s easy ground from here, just an undulating snow slope at a ridiculous altitude.

I believe that late in the day – dangerously, stupidly late in the day – on June 8, 1924, George Mallory & Andrew Irvine stood on that lonely patch of snow on top of the world, the first people to reach the summit of Mount Everest. (There, I said it!) It was probably sunset. The temperature was dropping. They were low on, or out of, oxygen. But, there they were, exuberant, embracing, on the summit of Everest.

And then the hard part began…they had to get back down.

What happened? What went wrong? Where did they fall, and what caused it? And, where is Andrew Irvine…and the camera?

I’ll save that for Part III of this story – stay tuned.