Now we’re in descent mode.

I already covered in Part I and Part II what I think happened on the uphill portion of Mallory & Irvine’s journey in 1924. And, now the hard part, the most dangerous part, the part when, statistically, most people die in the mountains: the descent.

As noted in Part II of the story, I believe George Mallory and Andrew Irvine reached the summit late in the day – dangerously, foolishly late in the day – on June 8, 1924. It was most likely sunset, or close to sunset. The temperature dropped as the sky became crimson. Monsoon storm clouds washed up and down the North Face of Everest, spitting snow and gusting wind from time to time.

And, Mallory & Irvine were exhausted. They had had a long, long day high on Everest, some thirteen or fourteen hours already above their high camp, which now sat 2,000 feet below them.

The first hour and a half of descent – coming off the summit pyramid and down to the Third Step – would have been smooth. The snow face below the final ridge is steep, and requires some careful climbing, but with the rope for safety Mallory & Irvine could have fairly easily followed their steps from the ascent down to the easier terrain at the Third Step.

The next 45 minutes would take them along easy ground again to the top of the Second Step. And, now, it really gets interesting.

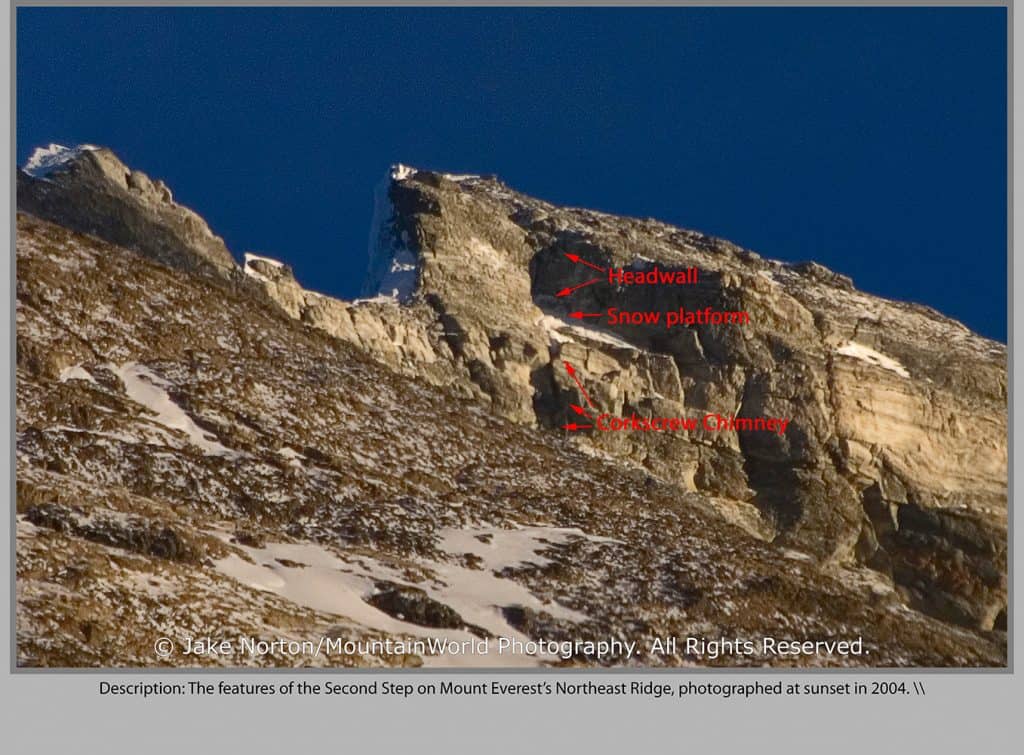

Today, the descent from the top of the Second Step is pretty straightforward. A bit daunting, for sure, but straightforward. We have generally solid fixed lines attached to pitons and anchors in the rock, and a short, exposed rappel takes us down to the snow platform above the Corkscrew Chimney. The only major hurdle – which sadly has been the end for some modern climbers – is having the presence of mind to choose the right fixed line to clip in to; some of them are old, tattered, no longer fixed to anchors, or don’t actually reach the snow platform. But, aside from that issue, we’ve got it easy today.

And, a final note: In 2000, I was speaking to the Boulder, Colorado, chapter of the Explorer’s Club, telling the story of Mallory & Irvine and our 1999 expedition. At the end, my friend Glenn Porzak told an amazing story. In the mid-1980’s, he was at an Alpine Club meeting, and had the opportunity to share lunch with a dapper octogenarian named Noel Odell. After chatting about climbing and life for some time, Glenn said he finally couldn’t resist, and asked the question of all questions: Did Odell see Mallory & Irvine atop the First, or Second, Step at 12:50 PM on June 8, 1924?

For Mallory & Irvine, though, it was of course a different situation. No fixed lines. No pitons, stoppers, pickets, cams, or any anchor devices to fix the rope or set a rappel. And, unfortunately, there are really no rocks or boulders on top of the Second Step to sling the rope for a rappel. The only option would be to lower and downclimb. (As an aside, I have never had much trouble seeing Mallory & Irvine climb up the Second Step, but have always struggled with how on earth they could get down it again.)

In August 1999, I was in Seattle with our historian, Jochen Hemmleb, going over the artifacts and helping with the creation of our expedition book, Ghosts of Everest. I hadn’t seen the artifacts we collected on the expedition since we left Basecamp, and thus had forgotten about the blood on Mallory’s lapels. I noticed it when Tap Richards and I took clothing samples from Mallory’s remains, but, in the excitement of everything, made only a mental note of it. Seeing the clothing again raised a question: The blood, to my untrained eye, seemed deliberately placed, almost blotted, rather than splattered. Perhaps, I wondered, it indicated a previous injury, something that happened earlier in the day…something that precipitated the final, deadly fall?

The next day, Jochen and I took the clothing to the King County Coroner. After examining the blood stains, his professional opinion backed up the amateur assumptions of Jochen and I: The bloodd stains were indeed blotted, not splattered, and thus most likely indicate Mallory having tended to an injury before the final fall; perhaps an injury to himself, perhaps to Irvine. This post-expedition discovery made me realize the descent of the Second Step in 1924 might not have gone smoothly:

In fading, evening light, with temperatures dropping rapidly, it’s time to move. Mallory, being the more skilled and experienced rock climber, uses the rope they carried to lower Irvine down the Second Step headwall to the mid-point snow platform. Once there, Irvine flips the rope around his waist to give Mallory a hip belay. As they did on the ascent, Irvine stands close to the rock, ready to be a human step-ladder for Mallory, reversing the courte-achelle they did on the ascent hours before.

Doing a reverse mantel, Mallory scuffs on his belly over the edge of the Second Step. His feet dangle in the air, his eyes nervously scanning the North Face which drops some 9,000 feet directly below him. He finds scant handholds, and relies mainly on the friction of his body on the rock to keep from falling. His feet flail, moving about in the air above Irvine’s head, hoping to make contact with that human ladder. There’s not much Irvine can do to help aside from giving verbal instructions, for if he uses his hands to guide Mallory’s feet, then Irvine would have to let go of the belay. So, he holds tight, gives directions, and hopes for the best.

Suddenly, Mallory slips. The weight of his body moving over the edge of the rock outstrips the force of friction, and his meager handholds do little to stop him. Mallory clatters over the edge, hitting Irvine while he frantically takes in rope on the belay. With a thud, Mallory slams into the snow platform. Fortunately, the snow here is just soft enough in the evening – having been softened by the warm rays of the setting sun – to absorb some of the impact and slow the fall. That, combined with Irvine’s hip belay, avert death for the two for now.

But Mallory is hurt; how could he not be after a fall like that? He and Irvine collect themselves, and tend to their injuries. However, there is not much time…the evening light is nearly gone, and there’s still a lot of mountain to descend before reaching the safety of Camp VI.

Moving more slowly now – thanks to Mallory’s injuries and perhaps Irvine’s, too – the pair descend carefully through the Corkscrew Chimney and across the easy, but horribly exposed, ledges below the Second Step and on toward Mushroom Rock. Mushroom Rock provides a spot for a brief respite. The urge to stop, to stay here and wait until dawn to complete the descent must have been strong. But, Mallory & Irvine must have known there was no way to survive the night without food and shelter. They had to keep climbing down the mountain.

From Mushroom Rock, thirty minutes of exposed traversing led them to the top of the First Step. As with all steep terrain, what is easy on the ascent is often a bit trickier on the descent. Following their earlier path on the ridge proper, Mallory & Irvine descend the First Step – slowly and carefully. It’s now dark, the nearly half moon providing just enough light to make out the terrain ahead. Perhaps an hour later, they’ve carefully picked their way down the First Step, and are welcomed by the “easy” terrain of the lower Northeast Ridge. The limestone ledges are wide here, the exposure lessened, and camp – still some 1,000 feet below – seems finally within reach.

In the failing light as the moon dips to the horizon, Mallory & Irvine here make the mistake many have repeated since: they choose the wrong gullies to descend. Ascending through the Yellow Band, coming from the bottom, both the Longland Traverse and the modern climber’s gullies are obvious lines to the ridge crest. However, from the top, there are many gully systems leading down into the Yellow Band, all looking roughly the same. Today, with decades of hindsight, we know to mark the exit of the gullies well so we can find the right ones on the descent. But, Mallory & Irvine were the first up here; there’s no way they would have known about this trap on the ridge.

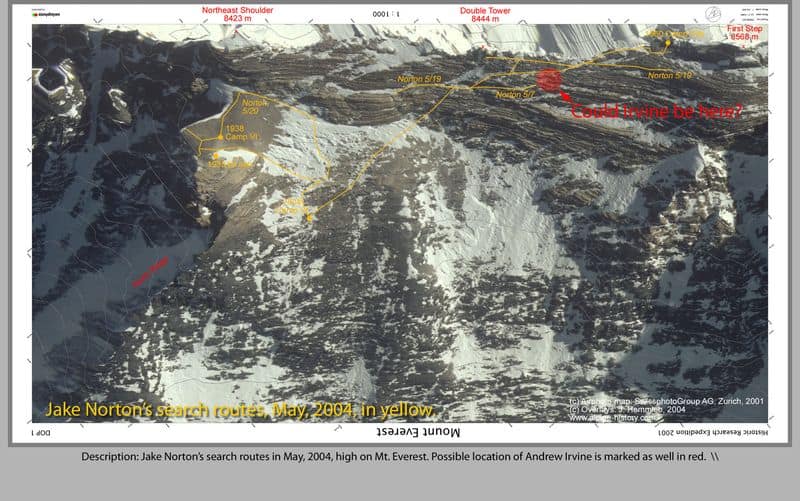

So, I think they chose the wrong set of gullies. The ones I believe they chose begin just below the ridge crest, roughly 200 meters down from the base of the First Step. Like all these gullies, they lead tantalizingly into the Yellow Band. Curious, I investigated this particular set during my search with Dave Hahn on May 7 and May 19, 2004. Climbing alone, I first set out into the gullies from the 1933 high camp, which I found in 1999. My thinking was predicated on the bits of information provided by Xu Jing, saying he had found a body while climbing from Camp VI to Camp VII in 1960. Since there was not really an established “route” through the Yellow Band at that time, I tried to just follow the most logical path, which led me up this particular set of gullies. Roughly 2/3 of the way from the 1938 Camp VI to the ridge crest, the gullies hit a short but steep cliffband. With no rope and miserable, slab snow conditions, I retreated back the way I had come. On the 19th, I explored the same gullies, entering them from the ridge crest below the First Step. From here, they are very enticing, welcoming even, and seem from this perspective to lead without issue all the way down through the Yellow Band. But, of course, they don’t terminating in the same short cliffband I encountered two weeks prior.

These are the gullies I think Mallory & Irvine may have mistakenly taken. In the dark, exhausted, it would be an easy mistake to make. After descending several hundred feet in the gullies, they would have hit my little cliffband. Again, it’s short, but steep, and the exposure is the entire North Face. Just as on the Second Step, Mallory & Irvine would have used the rope they carried, with Mallory lowering Irvine down the cliffband. Once safely down, Irvine would have belayed Mallory – the more skilled rock climber – with a hip belay, hoping the small horns of rock he slung the rope over would stop any fall.

And then he fell. Perhaps it was precipitated by the injury I think he sustained earlier. Perhaps it was simply exhaustion coupled with darkness and cold. Or maybe it was just carelessness. But, regardless, Mallory fell, and fell hard enough to sustain serious injury from the rope tied to his waist with a bowline-on-a-coil. (In 1999 we saw and documented severe bruising and rip damage from the rope pull on Mallory’s waist, telling visually the story of a big fall.) The rope came taught, catching on a horn or fin of rock. The impact through the old, static, hand woven line is hard, wrenching Irvine upward and slamming him into the small cliffband. He fights and holds onto the rope, straining to stop the fall, to stop his friend and companion from falling into oblivion.

And then, nothing. The strain disappears as suddenly as it began. The rope has broken, severed by the rock and the forces involved. Mallory is gone, cartwheeling down into darkness.

Irvine, though, is still alive. Probably injured, but alive. Terrified, but alive. He listens for any sound of Mallory; there is none. Only the eery silence of the high Himalaya on a cold, now moonless, night.

Irvine knows he needs to move, he needs to get down, get help, send a signal to Odell. Maybe Mallory is still alive, down in the darkness. But what to do? Irvine struggles for a while in the gully, his lack of climbing background amplified by the current situation. Maybe there’s another cliffband below? he wonders. If I’m not careful, I’ll end up just like George. He decides the best thing to do is to wait, wait for daylight, wait for Odell. He can last through the night, he thinks, if he can just find some protection from the unending winds. Above him is a small dihedral, facing the lee side, just big enough to provide some shelter. Irvine scampers up to it and wiggles himself in tight, his clothing buttoned up tight to offer all protection possible.

The cold sets in. Primitive, debilitating cold. It sets deep, icy tentacles penetrating to the bone. And soon, long before dawn, Irvine is gone, too, to be seen 36 years later by Xu Jing.

Is that what happened? Well, who knows. Certainly not me. As I’ve said many times before, it’s nothing more than my opinion, based on a lot of passion, thought, and time spent in that high terrain.

And, it is based on my solid belief that the Northeast Ridge – including the Second Step – was within their ability in 1924. At the upper limit, certainly, but still within bounds.

Additionally, my theory is based upon something we did not find with Mallory on May 1, 1999…Mallory’s daughter, Claire Mallory Milliken, told our expedition in 1999 that her mother, Ruth, said George made one promise to her in 1924: he would take a letter from her and a picture of her and bury it in the summit snows. We never found the letter or picture on Mallory in 1999. Noel Odell never reported those items having been left behind in 1924 at Camp VI. And, personally, I can’t imagine George would have left them anywhere but where he promised his wife he would.

The answer, Glenn said, came immediately, with a twinkle in Odell’s eye: There was never truly a doubt in my mind…they were on top of the Second Step.

By my count, there are at least three different groups searching for Irvine as we speak: Jochen Hemmleb, keeping it quiet; Duncan Chessell, making his search known; and one more I’ve caught wind of but have been asked not to mention.

With all that activity, I can only hope that soon we may know more. Irvine may be located, the old Kodak VPK around his neck. Images may be pulled from the film, showing triumph…or not.

Or, perhaps Irvine will remain hidden, the keeper of the answers to the greatest mystery of mountaineering.

Ultimately, the question of whether they reached the top or not doesn’t really matter. For me, it is the simple fact that they tried, that Mallory, Irvine…and Norton, Somervell, Odell, Hazard, Finch, Shipton, Smythe, Wager, Wyn-Harris, and all the others bothered to push their limits, to try what many said was impossible. To me, this is the nugget of importance in the whole story.

Mallory himself said it best, so to end I’ll share some of his most famous and favorite passages:

Is this the summit, crowning the day? How cool and astonished… Have we vanquished an enemy? None but ourselves. Have we gained success? The word means nothing here. Have we won a kingdom? No… and yes… We have achieved an ultimate satisfaction…fulfilled a destiny…. To struggle and to understand-never this last without the other; such is the law….

– George Leigh Mallory writing of “the Kuffner,” the Frontier Ridge of Mount Maudit in France (1911)The first question which you will ask and which I must try to answer is this, “What is the use of climbing Mount Everest?” and my answer must at once be, “It is no use.” There is not the slightest prospect of any gain whatsoever. Oh, we may learn a little about the behavior of the human body at high altitudes, and possibly medical men may turn our observation to some account for the purposes of aviation. But otherwise nothing will come of it. We shall not bring back a single bit of gold or silver, not a gem, nor any coal or iron. We shall not find a single foot of earth that can be planted with crops to raise food. It’s no use. So, if you cannot understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself upward and forever upward, then you won’t see why we go. What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy. And joy is, after all, the end of life. We do not live to eat and make money. We eat and make money to be able to enjoy life. That is what life means and what life is for.

– George Leigh Mallory, 1923, New York City

[NOTE: I’m sure this post will raise many questions, comments, and criticisms. Some may wonder why I don’t make much mention of the ice ax found by Percy Wyn-Harris in 1933. There will be other questions, and I welcome them all. Please write your thoughts and criticisms in the comments area, and I’ll do my best to respond to them quickly!]